Oliver Family

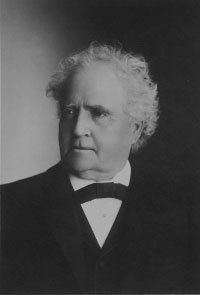

James Oliver

James Oliver

James Oliver, one of America’s most influential inventors and industrialists, was born on August 28, 1823 to George Oliver, a shepherd, and Elizabeth Irving, his wife, in the small village of Newcastleton, Scotland. Most of the residents of Newcastleton (or Copshaholm, as it was known in earlier ages), were very poor. The Olivers were no exception. Elizabeth came from a well-known Scottish family, which George had even worked for, but George was a simple shepherd, as much of his ancestors had been.

In 1830, one of James’ older brothers, John, restless and penniless, moved to America, working as a seaman to pay for his passage. After his arrival he wrote back to his family in Scotland, glowingly describing his new life in America. In 1834 two more of James’ siblings immigrated to America and also wrote back letters describing the good fortune and opportunities available. Finally, in 1835, after settling their debts with money from family in America, the Olivers set about getting ready for the whole family’s journey across the Atlantic.

The Olivers reached New York, and since they were accustomed to the beauty of Scotland, they found the city unattractive and spent as little time there as possible. They left by steamboa, traveling up the Hudson River before boarding another boat and traveling west on the Erie Canal, which had opened only a few years earlier. They stopped in Geneva, New York, at the farm of James Goodwin, who was John Oliver's father-in-law. This was the first time that the Olivers had plenty. Meat was served at every meal with potatoes, onions, and food they had not even seen before, like corn on the cob. James, thinking the corn on the ear was a new way of cooking beans, cleaned off the cob and asked that the ‘stick’ be refilled.

In 1836 the Olivers, lured by the inexpensive land available in the Midwest, moved further westward. The family originally settled in LaGrange County, Indiana, where their daughter Jane lived with her husband who owned 60 acres of farmland. Their son, Andrew, acquired 160 acres of virgin farmland from the government, and the family set out to help him clear it for farming.

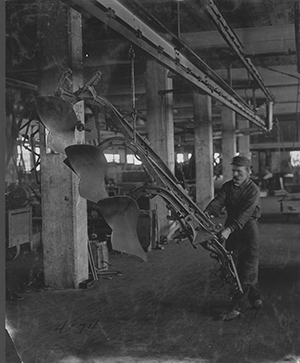

Oliver Plow

Oliver Plow

James moved farther west to Mishawaka due to greater opportunities, and was able to find good employment with the St. Joseph Iron Company until economic depression hit in 1837. After a bit of schooling and various jobs in the general area, James found work in a small foundry owned by the South Bend Blast Furnace Company of Mishawaka, where he was able to learn scratch castings and how to cast molds. After the company failed, James worked packing flour, eventually working as a cooper in the shop where the barrels were made, which gave him considerable experience and knowledge in carpentry. James became smitten by one of his coworkers, Susan Catherine Doty. After a few rebuffs, James persevered and won her hand, and on May 30, 1844 they were married.

James continued to work in a gristmill, and lived with his wife in a small cabin. James later describes this time as the happiest of their lives. He made improvements on the cabin, located on the banks of the St. Joseph River near Alger’s Island in Mishawaka. He then sold the cabin and moved to a larger parcel of land on the north side of the river. When the gristmill was destroyed by fire, James went to work in a blast furnace owned by William Gillen in the spring of 1845. Here, James was able to learn the molder’s trade, and he and Susan Catherine moved a third time to a larger home on ten acres of orchard on the south side of the river. In this time, they also had two children, Josephine, in 1846, and Joseph Doty, called J.D., in 1850. In 1858 they moved to South Bend.

In 1847, James went to work for the St. Joseph Iron Company after Gillen’s furnace failed financially. Here, James seized an opportunity to improve his financial station. Because the company was unable to keep up with their orders, James contracted with the company to produced the materials they needed, which he later admitted nearly killed him in the process. After the St. Joseph Iron Company changed hands, with his small financial gain, James was looking to possibly set up his own foundry, since he enjoyed working with plows. He loved working in the foundry, but also had a deep attachment to the land stemming from his boyhood in Scotland. While waiting for a train, he heard of a small foundry that was for sale on the West Race of South Bend.

Oliver Chilled Plow Works Advertisement

Oliver Chilled Plow Works Advertisement

In 1855, James Oliver and his co-worker Harvey Little had each purchased a one-fourth interest in the building. Cast iron plows were one item that this little foundry produced. Shortly after the purchase, the building was devastated by the rampaging waters of the St. Joseph River, but Oliver and Little managed to survive and the plant went back into operation. They were also able to purchase the second half interest of the building and renamed the business to the South Bend Iron Company. They purchased scrap iron for one and a quarter cents a pound and converted it to almost anything that could be made of cast iron at a charge of five cents a pound. At this time they produced iron window weights, caps and sills for windows, kettles, frying pans with legs and long handles, pulleys, stove castings, and grates. They also produced the metal strips that fit onto sled runners for the fledgling Studebaker Brothers Company.

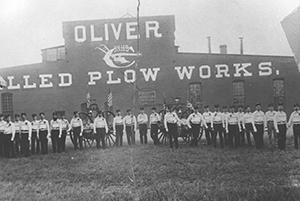

Oliver Chilled Plow Works Employees

Oliver Chilled Plow Works Employees

At this time, James continued to experiment with ways to produce a better plow and in 1857 he obtained his first patent from the U.S. Government entitled “Improvement in Chilling Plow Shares.” It covered James’ new way to process a plow point, or share, to an extremely hard surface. This first improvement made way for the many more patents that were to follow as the Oliver Plow became the most popular plow in the world.

The company continued to expand, and with it more property was purchased. The Oliver family moved closer to the business, purchasing a house on Main Street in 1858. In 1868, the house was moved to the back of the lot and a larger structure of brick was built in its place. In addition to producing many plows, the Oliver, Little, & Co. also produced fluted columns for Saint Mary’s College, two iron columns for South Bend resident and Vice President of the United States Schuyler Colfax, brackets for the city jail, and sewer crates for the city. In 1864 the company sold approximately 1,000 plows. With the Civil War in progress prices continued to rise as demands for production increased. The company also made 70 iron columns to hold up the Golden Dome structure in the University of Notre Dame’s Main Building. The Oliver Company was expanding and growing and by mid-1865 the staff was increased to plant capacity. At this time, J.D. Oliver, James’ son, was getting in on the company’s ground floor.

Oliver Row Homes

Oliver Row Homes

The company continued to expand and in 1876 the new plant, formally called the Perkins Farm, which consisted of 32 acres on the southwest edge of South Bend, started its engine and the plant went into operation. It consisted of five buildings with a total area of 200,000 square feet. Plans called for employment of 400 men who would cast 50 tons of metal into 300 plows daily as a new 600-horsepower Harris Steam Engine powered the machinery. Plow sales in 1878 reached 62,779 units, shipped from coast to coast. The size of the Oliver company simply overwhelmed its opponents and business kept expanding.

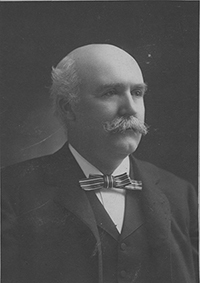

J.D. Oliver

J.D. Oliver

At 34, James’ son, J.D. Oliver, met Anna Gertrude Wells and their storybook romance culminated in marriage on December 10, 1884. When they returned from their honeymoon in California, they became the first occupants of Oliver Row, where they lived in #1.

J.D. had been working for the family business since he was 16 and had been the director of the factory since he was 20. At the time of his father’s death in 1908, J.D. was 58 and the transition from father to son was easily accomplished. In fact, most of the company’s financials were already managed by J.D., and after the death of his father he was elected President, Treasurer, and General Manager. At this point annual production was very high and the company was considering expanding to build a factory in Canada and begin exporting to Russia.

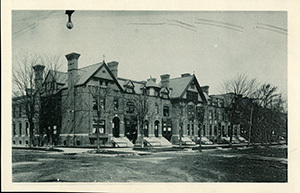

City Hall

City Hall

Alongside the company’s success, the Olivers also invested in civic architecture. At the turn of the century, the city of South Bend was in need of a new city hall that they could not afford, and James offered to build and lease the building to the city of South Bend. To the citizens of South Bend, the City Hall was though to be not just convenient and substantial but, most importantly, elegant.

Oliver Opera House

Oliver Opera House

The Olivers were also lovers of theatre and in 1885 they opened the doors to the Oliver Opera House. It cost $200,000 and was one of the finest in the United States. A few years after the opening of the Opera House, the Olivers built a hotel that would impress the visitors of South Bend. The Tribune wrote that the hotel was “the best and most magnificent hotel in Indiana, one of the finest in the United States, and the best in any city of 40,000 inhabitants in the world."

With the outbreak of World War I, attention was diverted from profits to fundraising in order to aid the troops on the front lines. J.D. Oliver crisscrossed the state of Indiana setting up fundraisers and selling bonds. After the war, however, demand for tractor-pulled farm implements increased rapidly and once again the Oliver Company underwent expansion. Oliver Chilled Plow Works expected to put 750,000 plows behind the 100,000 tractors International Harvester and Henry Ford and Son would build. At this time the company also introduced the innovative voluntary pension plan, providing for a pension and automatic retirement for an employee who had reached the age of 70 and had been with the company 20 years.

At the start of the 1920s business indicators looked strong for the Oliver Company. Disaster, however, was ahead. With a drop in farm prices, farmers were unable to pay debts and stopped buying agricultural implements. At this time, the company held the largest stock of manufactured goods and the largest stock of raw materials in its history, which were all purchased at inflated war-time prices. Since the company was in strong financial shape, they were able to withstand this crisis J.D. Oliver nevertheless fell victim to a four-month illness, described as ‘tired break-down,’ from which he never fully recovered.

With increasing competition in 1923, the Oliver Chilled Plow Works joined together with other manufacturers of different types of farm tools. A new company, to be known as the Oliver Farm Equipment Company, took over the Oliver Chilled Plow Works, the Hart-Parr Company of Charles City, Iowa, which manufactured tractors, and the Nichols and Shepard Company of Battle Creek, Michigan, which made threshing machines, corn pickers, and combines. On March 30, 1929 the Oliver Chilled Plow Works ceased to exist and the executive office posts of the new Oliver Farm Equipment Company were divided among the three merging companies, with J.D. Oliver serving as Chairman of the Board until he resigned on December 13, 1932.

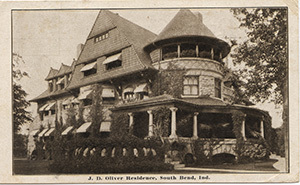

Copshaholm

Copshaholm

At the age of 83 J.D. Oliver died on August 6, 1933 at Copshaholm, the home he had named after the Olivers' ancestral village in Scotland and had moved into with his wife, Anna Gertrude, and their young family in 1897.

Bibliography

Danielson, Kay Marnon. Images of America: South Bend, Indiana. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publishers, 2001.

Palmer, John. South Bend, Crossroads of Commerce, The Making of America Series. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishers, 2003.

Romine, Joan. Copshaholm: The Oliver Story. South Bend, IN: Northern Indiana Historical Society, Inc., 1978